THE MAN WITH A THOUSAND FACES

by Marilyn Davis, ed.

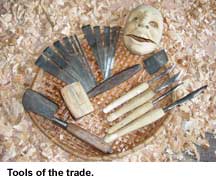

Naversen, an associate professor of theater at SIUC, specializes in scenic design. The masks, unpainted and in various stages of completion, are the fruits of a recent trip he made to the Indonesian island of Bali to learn mask carving from a master of the art. Sitting on his office floor, Naversen braces a partly finished mask between his feet, Balinese-style, and scrapes it gently with a chisel. He explains that he cannot sit for hours in this fashion without taking a break, the way the Balinese artisans can, but that yoga has increased his endurance. He shows me the tools of the trade: A small, angled hatchet called a timpas is used to rough out the mask and make the first cuts to start defining its features. Flat chisels (pahat) and rounded gouges (pengacap) in various sizes are used to flesh out the brow, cheeks, nose, and chin by creating grooves, ridges, and curves. They're also good for chinking out the openings for eyes and nostrils. "Large and small straight knives (pamutik) are employed as finishing tools, to smooth the mask; double-edged, curved knives (pangot) are ideal for refining eye sockets, nostrils, and lips and also for hollowing out the inside of the mask. "You want to get the mask as thin as the wood will permit," Naversen says. That's because these masks play a dominant role in Balinese theater, and they need to be comfortable. They are made, often, for a specific performer, who visits the mask-maker for "fittings" as the carving progresses. The mask is custom-designed to rest lightly on the front of the face. "In Western tradition our masks tend to go bigger and higher," Naversen notes.

"In Bali, theater and religion never separated," Naversen says. "Their plays are about the checks and balances of good and evil fighting with each other." Masked performers represent deities, kings, warriors, lovers. Performances typically feature music, dance, songs, and spoken interludes. "It's a little like our musical theater," Naversen says. "But they have a lot of mimed performances as well." A performer's every gesture carries a specific meaning. Balinese audiences "all know these stories and know the masks for each character," says Naversen, but each carver gives his masks unique touches, and performers differ in interpreting the same role. Audience members are connoisseurs of nuance, spotting small but telling variations in mask or performance style. Most famous for masks in Bali is the village of Mas, where Naversen and four other students were apprentices for several weeks to master woodcarver Ketut Molog. The studios in Mas produce masks, figurines, furniture--even, in a bit of cultural appropriation, totem poles and Scandinavian knick-knacks. "You want something made, they can do it," says Naversen. Although Naversen had little experience with wood carving before visiting Bali, he was already a mask enthusiast. He had collected masks from around the world and had made many masks of plaster, papier-mach, and modeling clay for theater productions. In Western culture, mask tradition stems from ancient Greek drama. "That's where we get tragedy and comedy masks," Naversen says. "They used to do plays in huge amphitheaters--5,000 people could sit in the theater at Epidaurus." Large masks conveyed the characters' emotions to the back rows, and miniature built-in megaphones enabled everyone to hear. In Renaissance drama, masks often designated the stock characters of Italian commedia dell'arte plays (where harlequin figures hail from). At Elizabethan masques--lavish musicals written for occasions at court--the noblemen and women in the audience, not just the performers, donned costumes and masks. Recently, Broadway has returned to the mask tradition with such blockbusters as "The Lion King," which features enormous, breathtaking puppets and masks by avant-garde artist Julie Taymor. Naversen's interest in masks, which extends beyond theater to psychology and anthropology, began in early childhood. "My mom would put on this little Halloween tiger mask and chase us around," he recalls with a grin. "If she'd just put the mask on and growl, it would scare us to death. She'd take off the mask and it would be OK. Put the mask back on, we'd be scared again." These irrational flip-flops between reassurance and fear fascinated him. "I've done this a lot with my nieces and nephews, and it's the same thing," he says. "When someone puts on a mask, suddenly you're not sure of that person any more. So I've always been interested in masks and their effect, and Halloween always was my favorite holiday. Maybe that's how I got into theater, I don't know." Something about wearing a mask allows people to do things they wouldn't ordinarily do and say things they wouldn't ordinarily say. "There's a theory that when you put on a mask, the neocortex, which governs reasoning, becomes less active," Naversen says. That would allow emotion to come to the fore--much like the effects of imbibing alcohol, he notes. No surprise, then, that many off-stage uses of masks remain theatrical in the broad sense. For instance, in Roman times, during the festival of Saturnalia, people would wear masks and demand treats--the origins of our Halloween. The Italian mask tradition subsequently became part of Carnival celebrations in Spain, South America, and New Orleans. In certain African and East European traditions, masks symbolize transformation in puberty rites. Artisans have created death masks of important rulers since the time of the pharoahs. In movies, masks disguise serial killers and superheroes alike. Other purposes for masks are more prosaic. Their use for hygiene goes back centuries: in the Middle Ages, doctors treating plague victims wore long-nosed masks stuffed with camphor-soaked wadding to fend off the stench of decay. The Inuit people devised leather masks with eye slits that functioned like sunglasses, to cut glare. In sports arenas, deep-sea dives, and military operations, variations on masks provide crucial protection. Masks can offer emotional or spiritual protection, too: they're sometimes used in counseling to help victims of abuse tell their stories. Shamans may use them to ward off evil spirits.

He signed up. Even the nightclub bombings in Kuta, Bali, in October 2002 didn't dissuade him from making the trip. Once there, he had no concerns about terrorism. "It was a paradise," he says--though one now threatened by economic hard times due to the drop in tourism. The students began their education by copying masks. "Ketut would carve on one side, and we would carve on the other," says Naversen. "For the first mask I made, Ketut carved about 75 percent of it, and it took about a week, including sanding. By the fourth mask, I carved about 75 percent, and for the last mask I made he would just look at what I was doing and make suggestions." Naversen documented the entire process, both in writing and in a video of Ketut producing a mask from start to finish. Carving remains much more laborious for Naversen than for the master. "Ketut could carve a mask within a couple of hours," he says. In Bali, masks are most often carved from pulai, a creamy, fine-grained wood worked while it is still green and soft. Finished masks are sanded and usually painted, often elaborately--a process that involves applying dozens of thin layers of paint. Sometimes they are embellished with hair, leather, mother-of-pearl, or other additions. At home, with pulai unavailable, Naversen has branched out to red alder from Oregon and experimented with catalpa wood (too hard, resulting in a cracked mask). Although he has painted and decorated one of his masks, he prefers the look of the unpainted wood. Naversen plans to pass along his new skill by teaching mask carving in independent study courses. He hopes enough students will learn so that wooden masks can be made for an upcoming production of "The Green Bird," an 18th-century commedia dell'arte play that was revived in 1996. He's organizing an interdisciplinary conference on masks and their uses, paired with a museum exhibit, both to be held at SIUC in 2005. And he intends to continue researching the cultural uses of masks. "In Bali, any mask used in a ritual performance has to be ceremonially cleansed," Naversen says. "Then a spirit is invited to come into the mask, to inhabit it. The performer is felt to be possessed by that spirit during the performance." It's a notion that, more broadly, may reflect our emotional responses to masks, he thinks. "Our psyche is very stimulated by masks," he says. "Somehow there has to be a spirit in a mask."

For more information, contact Ronald Naversen, Dept. of Theater, at (618) 453-3076 or rnav@siu.edu. |

Masks entertain us, protect us, sometimes scare

the dickens out of us. An SIUC scenic designer enthralled by them went

halfway around the world to learn the ancient art of "ukir

topeng"--Balinese mask carving.

Masks entertain us, protect us, sometimes scare

the dickens out of us. An SIUC scenic designer enthralled by them went

halfway around the world to learn the ancient art of "ukir

topeng"--Balinese mask carving. Life in

Bali is replete with ceremonies marking events large and small, public and

private. Towns, temples, and well-to-do individuals all sponsor

ceremonies, and mask performance (topeng, in Balinese) has long been an

integral part of them. These highly ritualistic dramas enact the religious

stories of Bali's Hindu culture.

Life in

Bali is replete with ceremonies marking events large and small, public and

private. Towns, temples, and well-to-do individuals all sponsor

ceremonies, and mask performance (topeng, in Balinese) has long been an

integral part of them. These highly ritualistic dramas enact the religious

stories of Bali's Hindu culture. At a theater

conference on masks that Naversen attended in 2001, he kept hearing

speakers mention the mask-making tradition of Bali. After some

investigation, he discovered that the

At a theater

conference on masks that Naversen attended in 2001, he kept hearing

speakers mention the mask-making tradition of Bali. After some

investigation, he discovered that the